The Sacrament of Holy Orders

And Michas said:

Stay with me, and be unto me a father and a priest,

and I will give thee every year ten pieces of silver,

and a double suit of apparel, and thy victuals.

Judges 17, 10

The Sacrament of

Holy Orders is the continuation of Jesus Christ’s priesthood, which He bestowed

upon His Apostles. This is why the Catechism of the Catholic Church refers to

the Sacrament of Holy Orders as “the sacrament of apostolic ministry” (Catechism

of the Catholic Church, 1536).

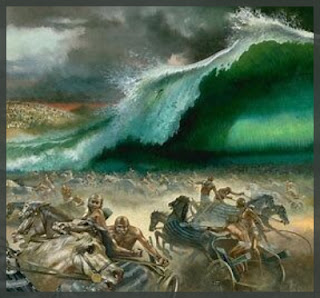

The priesthood of the New Covenant has its roots in the priesthood of the Old Covenant. God’s chosen people have constituted “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex 19:6; Isa 61:6). But from among the twelve tribes of Israel, God chose the tribe of Levi and set it apart to minister liturgical service (Num 1:48-53; Josh 13:33). The Levite priests were “appointed to act on behalf of men in relation to God, to offer gifts and sacrifices for sins” (Heb 5:1; cf. Ex 29:1-30; Lev 8). This priesthood was instituted to proclaim the Word of God and restore communion with God by sacrifice and prayer (Mal 2:7-9). However, this priesthood was powerless in bringing about salvation in the Christian meaning. The sacrifices for sin had to be repeated ceaselessly and were unable to achieve definitive sanctification and justification, which only Christ’s single sacrifice of himself could and would accomplish at the appointed time in salvation history (Heb 5:3; 7:27; CCC 1539, 1540).

In the New

Covenant, there are two participations in the one priesthood of Christ. Our

High Priest and unique mediator between God and humanity has made his Church

“be a kingdom and priests to serve his God and Father” (Rev 1:6). We who are

baptized “like living stones, are being built into a spiritual house to be a

holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus

Christ” (1 Pet 2:5). God’s chosen people in the New Dispensation are “a royal

priesthood, a holy nation, God’s special protection” (1 Pet 2:9). The entire

community of believers is as such priestly in their baptismal vocation

according to their particular spiritual gifts. Christians are anointed first

and foremost in the Sacrament of Baptism and then again when their baptismal

grace is perfected in the Sacrament of Confirmation.

As anointed priests in the Church, Christians are united to Christ and his sacrifice in the offerings they make of themselves in their daily lives. Paul exhorted the Christians in Rome to “offer [their] bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God, [their] spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1). The Second Vatican Council affirms, “[The laity] exercise the apostolate in fact by their activity directed to the evangelization and sanctification of men and to the penetrating and perfecting of the temporal order through the spirit of the Gospel. In this way, their temporal activity openly bears witness to Christ and promotes the salvation of men. Since the laity, in accordance with their state of life, live in the midst of the world and its concerns, they are called by God to exercise their apostolate in the world like leaven, with the ardor of the spirit of Christ.” (Apostolicam actuositatem, 2).

Catholics profess

Jesus Christ to be “the one (heis / εἷς) Mediator between God and man”

(1 Tim 2:5), by which St. Paul means He is the one who has ‘universally’

redeemed the world and has reconciled all humanity (Jew and Gentile) to God by

serving as a ransom for sin which was paid through the outpouring of his most

precious blood (2:6). Our Lord’s principal mediation in his humanity does not

preclude the mediation or intercession of the faithful in and through His

merits by prayer and sacrifice “so that everyone might be saved and come to the

knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:1-4). The apostle has no intention of

emphasizing that Jesus is the “one and only” (monos / μόνος) mediator in

the entire economy of salvation. The Christian faithful are indeed called to

participate in our Lord’s mediation as active and living members of His

Mystical Body who partake of the divine life (1 Pet 2:5; 2 Pet 1:3-4). This

prerogative is conferred on these members by right of adoption as sons and

daughters of God, who participate in Christ’s divine nature; since it is in his

humanity – not divinity – that Christ as Head of His Mystical Body intercedes

for us all before the Father as both eternal High Priest and sacrificial

victim.

The ministerial priesthood of bishops and priests and the common priesthood of believers participate each in their own way in the one priesthood of Christ (CCC 1546, 1547). While the common priesthood of the faithful “is exercised by the unfolding of baptismal grace –a life of faith, hope, and charity, a life according to the Spirit, the ministerial priesthood is at the service of the common priesthood. It is directed at the unfolding of the baptismal grace of all Christians. The ministerial priesthood is a means by which Christ unceasingly builds up and leads his Church. For this reason, it is transmitted by its own sacrament, the sacrament of Holy Orders” (CCC, 1547).

The ordained

minister acts in the person of Christ. Our Lord is present in the ecclesial

service of his anointed minister as Head of his body. The priest, by virtue of

the sacrament of Holy Orders, acts in persona Christi Capitis, representing the

person of Christ. “It is the same priest, Christ Jesus, whose sacred person his

minister truly represents. Now the minister, by reason of the sacerdotal

consecration which he has received, is truly made like the high priest and

possesses the authority to act in the power and place of the person of Christ

himself. Christ is the source of all priesthood: the priest of the old law was

a figure of Christ, and the priest of the new law acts in the person of Christ”

(CCC, 1548).

The ministerial

priesthood is a divine office that extends from the common priesthood of the

faithful through the sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation. This is an office

that our Lord has committed to his pastors to serve as shepherds of his flock

in his name and in him. It depends entirely on Christ and on his unique

priesthood for the good of all people and the communion of the Church. The

sacred power of Christ is communicated to the ordained minister through the

sacrament of Holy Orders. The exercise of this authority in the divine office

“must therefore be measured against the model of Christ, who by love made

himself the least and the servant of all” (CCC 1551). The ministerial

priesthood acts in the name of the whole Church when offering to God the prayer

of the Church, above all the Eucharistic sacrifice (CCC 1552). “The prayer and

offering of the Church are inseparable from the prayer and offering of Christ,

her head; it is always the case that Christ worships in and through his Church.

The whole Church, the Body of Christ, prays and offers herself ‘through him,

with him, in him,’ in the unity of the Holy Spirit, to God the Father. The

whole Body, caput et membra, prays and offers itself, and therefore those who

in the Body are especially his ministers are called ministers not only of

Christ but also of the Church. It is because the ministerial priesthood

represents Christ that it can represent the Church” (CCC, 1553).

Through the

Sacrament of Holy Orders priests “share in the universal dimensions of the

mission that Christ entrusted to the apostles.” The spiritual gift they have

received in ordination prepares them for the fullest universal mission of

salvation, that is to the ends of the earth, to preach the Gospel and minister

the sacraments (Mt 28:19-20; Acts 1:8). (CCC, 1565) It is in the Eucharistic

assembly of the faithful (synaxis) that ordained priests exercise their divine

office in the “supreme degree”… “acting in the person of Christ and proclaiming

his mystery, they unite the votive offerings of the faithful to the sacrifice

of Christ their head, and in the sacrifice of the Mass, they make present again

and apply, until the coming of the Lord, the unique sacrifice of the New

Testament, that namely of Christ offering himself once and for all a spotless

victim to the Father” (CCC, 1566).

Priests are called

“to the service of the People of God.” Together with their bishop, they constitute

a unique “sacerdotal college” (presbyterium) in which they fulfill all their

duties. Priests can exercise their ministry only on “dependence on the bishop

and in communion with them.” The vow of obedience priests make to the bishop at

the time of ordination and the “kiss of peace” at the end of the ordination

liturgy signifies they are in communion with him as his fellow workers in

Christ (CCC, 1567). “The unity of the presbyterium finds liturgical expression

in the custom of the presbyters’ imposing hands, after the bishop, during the

Ate of ordination” (CCC, 1568).

Finally, the Sacrament of Holy Orders also includes the ordination of deacons. They are situated at a lower level of the Church hierarchy. These candidates also receive the imposition of the bishop’s hands “not unto the priesthood, but unto the ministry” to serve the Church. Not unlike the priest, the deacon is a co-worker with the bishop together with the priest (CCC, 1569). Moreover, deacons also serve in Christ’s mission in a special way apart from the common priesthood of the faithful. “Among other tasks, it is the task of deacons to assist the bishop and priests in the celebration of the divine mysteries, above all the Eucharist, in the distribution of Holy Communion, in assisting at and blessing marriages, in the proclamation of the Gospel and preaching, in presiding over funerals, and in dedicating themselves to the various ministries of charity” (CCC, 1570).

The ordinations of

bishops, (selected by the pope), priests, and deacons preferably take place in

a cathedral on Sunday. All three ordinations take a proper place in the

Eucharistic liturgy (CCC, 1571). “The essential rite of the sacrament of Holy

Orders for all three degrees consists in the bishop’s imposition of hands on the

head of the ordinand and in the bishop’s specific consecratory prayer asking

God for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit and his gifts proper to the ministry

to which the candidate is being ordained” (CCC 1573).

The effects of the

Sacrament of Holy Orders are the indelible character and the grace of the Holy

Spirit. This sacrament “configures the recipient to Christ by a special grace

of the Holy Spirit, so that he may serve as Christ’s instrument for his Church.

By ordination one is enabled to act as a representative of Christ, Head of the

Church, in his triple office of priest, prophet, and king. As with the

sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation, the Sacrament of Holy Orders “confers

an indelible spiritual character and cannot be repeated or conferred temporarily”

(CCC, 1582). Although an ordained person could be discharged from his office

for grave reasons, “the character imprinted by ordination is forever. The

vocation and mission received on the day of his ordination mark him

permanently” (CCC, 1583). It is by the grace of the Holy Spirit proper to this

sacrament that the ordinand is configured to Christ as “Priest, Teacher, and

Pastor, of whom the ordained is made a minister” (CCC, 1585).

The Sacrament of

Holy Orders and the ministerial priesthood have a biblical basis. We find the

verb form for the noun hiereus or ἱερεύς in the New Testament. The word means

“priest” or one who “sacrifices to a god.” Paul writes to the church in Rome:

“Nevertheless, brethren, I have written the more boldly unto you in some sort,

as putting you in mind, because of the grace that is given to me of God, That I

should be the minister of Jesus Christ to the Gentiles, ministering

(hierourgounta / ἱερουργοῦντα) the gospel of God, that the offering up of the

Gentiles might be acceptable, being sanctified by the Holy Ghost” (Rom

15:15-15, KJV). What we literally have is “to be a minister of Christ Jesus to

the Gentiles, ministering as a priest the gospel of God” (NASB), “the priestly

duty of proclaiming the gospel of God” (NIV), or “in the priestly service of

the gospel of God” (ESV).

The Revised

Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE) has this: “But on some points I have

written to you very boldly by way of reminder, because of the grace given me by

God to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles in the priestly service of

the gospel of God, so that the offering of the Gentiles may be acceptable,

sanctified by the Holy Spirit.” Thus, the ministers of the New Covenant were

essentially priests and had priestly tasks. The supreme act of theirs was to

offer up the Eucharistic sacrifice to God in worship (1 Cor 10:16, 18, 20;

11:26; Heb 13:10, 15). There is no ministerial priestly function ascribed to

deacons, but there is to apostles, bishops, and elders.

Our Lord Jesus

definitively chose and sent his apostles to act like priests, or “mediators

between God and men.” For instance, after the Resurrection, our Lord appeared

to the apostles and said to them: “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent

me, even so, I send you.” And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and

said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they

are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained”(Jn 20:21-23).

On this occasion, Jesus communicates or transfers the sacred power to forgive

and retain sins. The apostles are to do what the Lord has done in his priestly

ministry with divine authority. The power or authority Jesus invests in them is

the one he has been invested in by God the Father in his humanity (Mt 5:17-26).

Ministering the

Sacrament of Reconciliation is a ministerial priestly task that is rooted in

the Old Covenant. For example, ‘ but he shall bring a guilt offering for

himself to the Lord, to the door of the tent of meeting, a ram for a guilt offering.

And the priest shall make atonement for him with the ram of the guilt offering

before the Lord for his sin which he has committed; and the sin which he has

committed shall be forgiven him’ (Lev 19:21-22, RSVCE). The ordination of the

New Covenant priests, therefore, began with Jesus and the apostles. The

Sacrament of Holy Orders was instituted by Christ himself.

The Scriptures

reveal that the ordained ministers of the nascent New Covenant Church had a

share in Christ’s priestly ministry and authority that originated from the

Father. Jesus says he does nothing of his own authority. Likewise, the apostles

will do nothing on their own authority but on the same authority that comes

from God (Jn 8:28). The father’s authority is transferred to the Son. The Son

does not speak on his own. This is a transfer of divine authority (Jn 12:49).

Jesus gives to his apostles what the Son has been given from the Father (Jn

16:14-15). The authority isn’t lessened or mitigated. Jesus declares to His

apostles, “He who receives you, receives Me, and he who rejects you, rejects Me

and the One who sent Me” (Mt 10:1, 40). Jesus gives the apostles the authority

to make visible decisions on earth that will be ratified in heaven (Mt 16:19;

18:18). The power to “bind and loose” was given to the priests of the Old

Covenant. Jesus tells his apostles that “he who hears you, hears me” (Lk

10:16). When we listen to our bishop on matters of faith and morals, we listen

to Christ whom he represents.

The Christian faith

is built upon the foundation of the apostles. The word “foundation” shows that

the apostolic teaching authority does not die with the apostles but carries on

through a physical line of succession (Eph 2:20). As soon as Jesus ascends into

heaven Peter implements apostolic succession. Matthias is ordained with full

apostolic authority (Acts 1:15-26). Only the Catholic Church can demonstrate an

unbroken apostolic lineage to the apostles in union with Peter through the

Sacrament of Holy Orders and thereby claim to teach with Christ’s own

authority.

At the outset, one

had to be ordained by an apostle to witness with the apostles and teach with

the authority of Christ which our Lord had invested in them (Acts 1:21-23).

This apostolic authority is transferred through the imposition of hands and has

been extended beyond the original Twelve as the Church has grown (Acts 6:6).

Paul himself becomes an ordained minister by the laying on of hands (Acts

9:17-19). The sacrament of ordination is necessary to invest Christ’s authority

in the ordinand. The apostles and newly-ordained men appointed elders (Acts

14:23). Preachers of the Gospel must be sent by the bishops in union with the

Church with the authority that can be traced back to the apostles (Acts

15:22-27). Paul is referring to the Sacrament of Holy Orders when he writes

that “God has commissioned certain men and sealed them with the Holy Spirit as

a guarantee” (2 Cor 1:21-22).

It is Paul and the

council of elders that ordain Timothy (1 Tim 4:14). Again, apostolic authority

is transferred through the laying on of hands. And Timothy himself is

instructed by Paul on how to properly ordain someone by the imposition of hands

(1 Tim 5:22; 2 Tim 1:6). Paul uses the word episkopēs (ἐπισκοπῆς) which

means “bishop” and thereby requires an office (1 Tim 3:1). Paul’s use of this

Greek word presupposes the office of the bishop shall carry on after his death

by those who will succeed him through the sacrament of ordination until Christ

returns.

I wish to conclude

by explaining how it is that Catholics call ordained priests “Father.” Dr.

Scott Hahn tells us that in the Old Testament the priesthood can be divided

into two periods: the patriarchal and the Levitical. The patriarchal period is

covered in the Book of Genesis while the Levitical period begins in Exodus.

These two periods differ significantly. “Patriarchal religion was firmly based

on the natural family order, most especially the authority handed down from the

father to the son – ideally the firstborn – often in the form of the ‘blessing’.”

(See Genesis 27.) There is no separate

priestly institution or caste as there is from the time of Moses, as well as no

temple and prescribed sacrifice. “The patriarchs themselves build altars and

present offerings at places and at times of their own choosing (See Gen 4:3-4;

8:20-21; 12:7-8). Fathers are empowered as priests by nature.”

Dr. Hahn continues:

“There are vestments associated with the office. When Rebekah took the garments

of Esau, her firstborn, and gave them to Jacob, she was symbolically transferring

the priestly office (Gen 27:15). We see the same priestly significance, a

generation later, in the ‘long robe,’ Jacob gave to his son Joseph” (See Gen

37:3-4). Thus, fatherhood is the original basis for the priesthood. “The very

meaning of priesthood goes back to the father of the family – his

representative role, spiritual authority, and religious service… priesthood

belonged to fathers and their ‘blessed’ sons.” On the other hand, the Levitical

priesthood “became a hereditary office reserved to the cultural elite. And the

home was no longer the primary place of priesthood and sacrifice” (Signs of

Life: 40 Catholic Customs and Their Biblical Roots: Doubleday, 2009).

Still, when a Levitical priest comes knocking at Micah’s door, he pleads, “Stay

with me, and be to me a father and a priest” (Jdgs. 17:10).

When Paul said, “I

became your father through the gospel,” he was referring to himself as being a

priest. The community of believers in Corinth comprises his sons and daughters

and heirs to the kingdom of heaven. Not unlike Paul, his successors in the

Catholic Church – through the Sacrament of Holy Orders – are fathers and

priests by their role of representing Christ, their spiritual authority, and

religious service: the preaching of the gospel and ministration of the

sacraments for the family in the house of God which is the Church.

EARLY SACRED

TRADITION

“Our apostles also knew, through our Lord Jesus Christ, that there would be

strife on account of

the office of the episcopate. For this reason, therefore,

inasmuch as they had obtained a perfect

foreknowledge of this, they appointed

those [ministers] already mentioned, and afterward gave

instructions, that

when these should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed them in their

ministry.”

St. (Pope) Clement of Rome,

1st Epistle to the Corinthians, 44:1-2

(c. A.D. 96)

“See that ye all follow the bishop, even as Jesus Christ does the Father,

and the presbytery as ye

would the apostles; and reverence the deacons, as being the institution of God. Let no man do

anything connected with the Church without

the bishop. Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist,

which is [administered] either

by the bishop, or by one to whom he has entrusted it. Wherever the

bishop shall

appear, there let the multitude [of the people] also be; even as, wherever

Jesus Christ

is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful without the

bishop either to baptize or to celebrate

a love-feast; but whatsoever he shall

approve of, that is also pleasing to God, so that everything

that is done may

be secure and valid.”

St. Ignatius of Antioch,

Epistle to the Smyraens, 8

(c. A.D. 110)

“Since, according to my opinion, the grades here in the Church, of

bishops,

presbyters, deacons, are imitations of the angelic glory, and of that economyz

which, the Scriptures say, awaits those who, following the footsteps of the

apostles,

have lived in the perfection of righteousness according to the Gospel.”

St. Clement of Alexandria,

Stromata, 6:13

(A.D. 202)

“And before you had received the grace of the episcopate, no one knew you;

but after

you became one, the laity expected you to bring them food, namely instruction

from

the Scriptures…For if all were of the same mind as your present advisers, how

would

you have become a Christian, since there would be no bishops? Or if our

successors

are to inherit the state of mind, how will the Churches be able to hold

together?”

St. Athanasius,

To Dracontius, Epistle 49:2,4

(c. A.D. 355)

“The Blessed Apostle Paul in laying down the form for appointing a bishop

and creating by his

instructions an entirely new type of member of the Church, has

taught us in the following words the

sum total of all the virtues perfected in

him:–Holding fast the word according to the doctrine of faith

that he may be

able to exhort to sound doctrine and to convict gain savers. For there are many

unruly men, vain talkers and deceivers. For in this way he points out that the

essentials of

orderliness and morals are only profitable for good service in

the priesthood if at the same time the

qualities needful for knowing how to

teach and preserve the faith are not lacking, for a man is not

straightway made

a good and useful priest by a merely innocent life or by a mere knowledge of

preaching.”

St. Hilary of Poitiers,

On the Trinity

(A.D. 359)

“There is not, however, such narrowness in the moral excellence of the

Catholic Church as that I

should limit my praise of it to the life of those here

mentioned. For how many bishops have I known

most excellent and holy men, how many,

presbyters, how many deacons, and ministers of all kinds of

the divine

sacraments, whose virtue seems to me more admirable and more worthy of

commendation

on account of the greater difficulty of preserving it amidst the

manifold varieties of men, and in this

life of turmoil!”

St. Augustine,

On the Morals of the Catholic Church, 69

(A.D. 388)

“It is you who have

stood by me in my trials; and I confer a kingdom on you,

just as my Father has conferred one on me, that you may eat and drink at my

table in my kingdom; and you will sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of

Israel.”

Luke 22, 28-30

.webp)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)